Thor Heyerdahl Jr. is the eldest son of the world famous adventurer who led the Kon-Tiki expedition. As well as being chairman of the board at the Kon-Tiki Museum for 22 years, he has had a long career as a marine scientist: live-tagging whales and polar bears, and even working as a fishing advisor to Fidel Castro in Cuba. Thor Heyerdahl Jr. looks back on his incredible travels with his father, and how it was to be the son of a legend.

Growing up as the son of a world famous personality was both challenging and exciting. At the age of 17, Thor Heyerdahl Jr. joined his father on the expedition to Easter Island in 1955. While they were there, tragedy struck—and it took 50 years to heal the wounds.

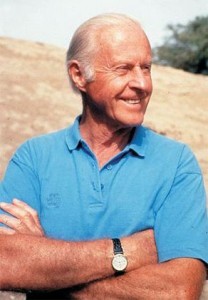

The Father: Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002)—The Adventurer

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl is internationally recognised for leading the Kon-Tiki expedition, where he sailed 8,000 km by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands. The Norwegian scientist proposed that natives of South America sailed across the Pacific Ocean to populate the Polynesian islands. Instead of the passive researcher’s theorising, Heyerdahl built and sailed a primitive raft to test it himself. Born on 6 October 1914, he decided to become an explorer at the age of 8. In 1933, he began studying biology and geography at the University of Oslo, where he privately studied Polynesian culture. The university helped organise a study trip to Polynesia, and he married Liv Coucheron-Torp on Christmas Eve 1936, leaving for Tahiti the following day.

The Son: Thor Heyerdahl Jr.—’A Product of Paradise’

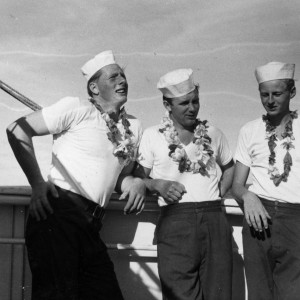

Thor Heyerdahl Jr., Easter Island, 1955.

“I’m produced in Fatu-Hiva—a product of paradise you could say,” smiles Thor Heyerdahl Jr. Between 1937 and 1938, Thor and Liv lived self-sufficiently on the mountain island of Fatu-Hiva. Thor noticed that the prevailing winds and ocean currents from America determined the flora and fauna, and he began to doubt theories that the Polynesian’s forefathers had arrived against the wind from Asia; they may have come via an alternate route. In 1938, Liv and Thor returned to Oslo and had their first son, Thor Heyerdahl Jr.

In 1939, “my father took my mother and myself, as a 1-year-old kid, to British Columbia in the Pacific coast of Canada.” He wanted to study the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast because he suspected they shared similarities with the Polynesians. In keeping with existing research, he found there had been two migrations to the Polynesian islands, but claimed the oldest of these had not arrived from Asia by canoe, but by balsa wood raft from South America. This was a controversial theory. The accepted belief was that no American type of prehistoric vessel could have successfully made that journey; Thor Heyerdahl decided to try it.

First Memories from World War II

During the Second World War, Heyerdahl’s family had to live in Canada. Sentiment towards Norwegians was mixed at the time of the Nazi occupation of Norway. “We were disrespected because of lack of resistance,” Thor says. “It was pretty tough. We felt very unpopular until we got known for the heavy water sabotage in Telemark, and when Norwegian resistance was really established and my father volunteered to join the Norwegian resistance forces.” His father trained as a parachutist and went to Europe to drive out the Nazis. Thor said farewell to his father at the age of 4 in 1942. He remembers his mother saying to him and his younger brother Bjørn: “Boys, now take a close look at your father. Pinch him, smell him, I want you to know what a wonderful father you had, this may be the last time you ever see him.”

Thor Heyerdahl Jr.: “That’s the first clear recollection I have of my childhood. That made an enormous impression on me. So then, for the rest of the war, 3 years, we never got a word from my father.”

The family was reunited in Oslo in 1945, yet they saw little of Thor Heyerdahl as he arranged the Kon-Tiki expedition. Later in 1949, Thor and Liv divorced, though they retained good relations. “I am proud to be the son of my father, but I’m even more proud to be the son of my mother. I consider my mother superior intellectually to my father,” Thor Heyerdahl Jr. remarks. Though absent from much of Thor Heyerdahl’s papers, Liv participated in many of his adventures. Several years after the separation with Heyerdahl, Liv fell in love with another adventurer and writer, James Stillman Rockefeller Jr. The couple got married in 1956 in the US.

Son of an Adventurer

The Kon-Tiki expedition, a 1947 journey by raft across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands, made Thor Heyerdahl famous. Thor Heyerdahl Jr. highlights the context of his father’s fame: “You must remember that in these post-war years, before science fiction, before landing on the moon…we were still worn out from the experiences of the war, death, tragedy, the world in ruins. And here, two years after the Nazi capitulation, six handsome young men sailing with the trade wind across the world’s largest ocean, landing on a Polynesian reef with coconut palms, beautiful Hula girls, you could say that this was a dream come true. For once, something exciting, thrilling, adventurous happened, that had nothing to do with the war. So he got much more attention then than he would have gotten today, I’m convinced.” As Thor Heyerdahl Jr. entered high school, being the son of a famous man became challenging:

“It was a challenge to my ambitions, bearing the same name as my father, being in many respects similar to him. It was a burden.”

“I remember we had a father-son talk”, Thor notes, in which he got the advice: ‘Whatever you decide to do, don’t become a scientist.’ “I wanted to avoid archaeology, avoid anthropology, avoid sailing in my father’s wakes.” While his father received 16 honorary PhDs but had no formal education, Thor later graduated as a Master of Science and established his own career, “so there’s no reason for any inferiority complex”. He even cooperated with his father, advising him about the wind and current systems of the Atlantic.

Tragedy on Easter Island in 1955

When Thor was 17, his father asked him to join him on his archaeological expedition to Easter Island. “He had chartered a Norwegian trawler, a fishing boat, manned it with a crew of 16,” Thor recalls, “but, as he said, ‘I lack a deck boy’,” Thor laughs. “That was a fantastic adventure—a whole year as a late teenager on an expedition like that!” But he didn’t see much of his father as he had to work, just like any other crew member.

Thor Heyerdahl Jr.: “I didn’t want to be ‘Papa’s son’—I wanted to be respected by the crew as one of them.”

Thor Heyerdahl Jr. (on the right) with his peers on the Easter Island expedition in 1955.

On Easter Island, father and son were referred to as Kon-Tiki Nui Nui (‘big Kon-Tiki’) and Kon-Tiki Iti Iti (‘little Kon-Tiki’). They got a very friendly reception by the local population on the island. “They were not used to visitors”, Thor explains, “Easter Island is still the most isolated inhabited place on Earth.” They established very good relations and the crew wanted to show their gratitude. What follows, Thor says, is “the saddest story of my life, and the happiest, in the very same story.”

They invited all the children aboard the boat and sailed around the island, “which was a tremendous experience of course, to them.” The village was on the south of the island and the crew’s camp was on the north coast. They disembarked at camp and had a BBQ, or curanto, with the children. All danced, sang and played, and then everyone returned to the vessel and sailed to the village. “In the Pacific you always have these swells, drowsy swells, but every now and then comes a huge wave, caused by a tsunami or earthquake, so I yell at the steersman ‘slow down the engine, here comes a huge wave!’ and then, too late, we dug into it as it was breaking on the beach.” Immediately the boat filled with water. “I got a shock of course, but I wasn’t scared really because I expected all these Polynesian kids to swim like fish. I thought, well, it’s just a question of getting ashore; to swim into the beach was too far, the nearest cliffs were closer, but treacherous because of sharp lava rocks like broken glass.” Thor was covered in blood from being thrown onto the rocks, and by his side a little girl lay bleeding. He then realised many of these children couldn’t swim, or were too panicked. This was also observed from camp, so the expedition members swam out to the site, picked up children and pulled them ashore.

“Except for two: one girl and one boy, only 12 years both of them, they sank down to 30 metres. None of us were able to dive that deep down, but one of the natives, he managed. But it was too late. They’d both drowned, and the schoolteacher drowned. So this was absolutely, indescribably tragic.”

Thor’s father, as expedition leader, had to hold a hearing and produce an official report. Thor remembers his father pressed him: “‘you were a crew member, a professional sailor, did you think of more than rescuing your own life?’” Thor was in deep shock, “‘well Papa I just don’t remember, it’s completely out of my mind'”.

“I remember my father was very disappointed,” Thor says, “he had to write that his own son was one of the two responsible crew members.” As a result, in the Aku Aku book, “there are three lines just mentioning I was in the boat but what I did or didn’t do, he doesn’t say a word about it. This has been embarrassing for me all my life.” Thor Heyerdahl Jr. is still devastated: “We should have been slower. Absolutely. I have avoided going back to Easter Island for more than half a century, because not one day has passed without remembering this tragedy.”

‘Gracias Para La Vida’—Thank You For Life

Several years after Thor’s father died in 2002, Gyldendal, a Norwegian publishing house, and NRK asked Thor to guide them around Easter Island as the only living expedition member—Thor reluctantly returned. While in Easter Island they attended mass at a church. “A beautiful ceremony,” Thor recalls, “it put me in a solemn mood. Leaving the church, somebody yelled after me, ‘Kon-Tiki iti iti! Kon-Tiki iti iti!’”.

After all these years, someone recognised him. Thor turned to see a middle-aged woman with reddish hair, who flung her arms around him. She squeezed him tightly and noted that he didn’t recognise her:

“‘Don’t you remember the accident in Anakena Bay, back in cincuenta y cinco (55)?’

‘Oh yes, not one day has passed without that bothering my mind.’

‘Do you remember the little girl who tried to climb up on you?’

‘Ah do I remember—oh yes, there was a little girl who tried to climb up on my shoulder…’

‘Do you remember that you grabbed my hand, and placed it on your shoulder, and told me just to hang, and you towed me ashore?’

And then it came to my mind. Strangely then, all the details, everything came back.”

“Then she said in Spanish, gracias para la vida, ‘thank you for life’. Then I started crying. And she cried. And that is probably the happiest moment of my life.”

Thor was filled with relief. He realised he hadn’t failed; he had done what he possibly could.

“I’ve never seen her since,” Thor muses. Every year after, Thor Heyerdahl Jr. has returned to Easter Island, now with a feeling of happiness.

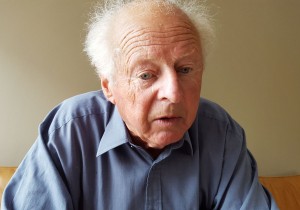

Thor Heyerdahl Jr.—A Man Who Found His Path

With his own identity established later in life, Thor’s experience of his father’s fame was no longer a burden: “I made a career as a scientist, specialising in marine mammals, live-tagging polar bears, whales, being a fishery expert for the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) under the United Nations, a fishing counsel for Fidel Castro in Cuba!” Thor has made his peace with his father’s fame: “I have a very relaxed attitude towards being the son of a famous man.”

Thor Heyerdahl Jr. is content with life. He is on pension but still active in the Kon Tiki Museum working as a senior scientist. He mostly spends his time in his remote house in the woods outside of Oslo. “Now I’m a lumberjack”, he says happily. “I work manually, not as an academic anymore, and I enjoy using my own body, getting worn out, sweat and blood and blisters and all that, so I’m very happy with my life really, the way it has been and the way it is.”

The Kon-Tiki Expedition by Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl Sr. launched the balsa wood raft in 1947. It was named the Kon-Tiki after a legendary seafaring sun-king common both to the islands of Polynesia and the old Inca kingdom. With 5 other men aboard, Thor left the port of Callào in Peru and sailed 8,000 km across the Pacific Ocean over the course of 101 days, landing on the Raroia Atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago. This astonishing voyage proved that Polynesia was well within the range of prehistoric South American seafarers. “The expedition did not prove that it had been done but that it was possible, and not only possible but simple; as long as you stay afloat you drift with the trade winds and the equatorial current, you end up on the other side of the ocean, whether you want to or not,” Thor Heyerdahl Jr. explains.

An Oscar-winning film about the Kon-Tiki was released—Norway’s only feature film to win an academy award to date.

Heyerdahl’s book The Kon-Tiki Expedition has been translated into 70 languages, selling at least 100 million copies over the world.

Thor Heyerdahl used the earnings from his books and documentaries to finance further expeditions: making discoveries in the Galapagos Islands (’52), Easter Island with his son (‘55–56), crossing the Atlantic on the reed boat Ra (‘69–70) and the Indian Ocean on Tigris (’78). He was actively involved in archaeological projects until he died in Italy in 2002. He received a state funeral in Oslo.

Visit the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo

At the Kon-Tiki Museum you can experience up-to-date exhibits on Thor Heyerdahl’s expeditions: Kon-Tiki, Ra, Tigris, the fabled Easter Island, Fatu-Hiva, Tùcume, and Galapagos. See the original vessels, tour a 30-metre cave, and discover an underwater exhibit with a 10-metre model of a whale shark. Thor Heyerdahl’s archives at the museum are included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register. The museum is still engaged in research in the Pacific area.

Watch the original, Oscar-winning Kon-Tiki documentary at the museum cinema, with daily screenings at noon.

The Kon-Tiki museum is located at Bygdøy peninsula in the Oslo area. Find your ticket here.

Bill Clinton visits the Kon-Tiki Museum. The former US President had a tour of the Kon-Tiki museum with Thor Heyerdahl Jr. in the late nineties. Arriving in a helicopter, he said, ‘this is a private visit so no journalists, no photographer, no security, just you and me’. Clinton interrupted Thor as he began explaining the exhibits, saying, ‘well I’ve read all your father’s books’.

Bus: Number 30 from Oslo centre.

Ferry: In the summer you can take the 15-minute ferry from Rådhuskaia.

The museum is open every day except 17 May, 24–25 and 31 December, and 1 January.

Text: Georgina Berry / Photos of Thor Heyerdahl Jr.: Dina Johnsen / Archive photos: courtesy of the Kon-Tiki Museum